In the dynamic environment of a dental laboratory, where the high-pitched whine of a milling unit meets the focused silence of the bench, the true quality of a prosthesis is born. It isn’t just about owning the latest scanner, the finest zirconia discs, or the most advanced casting equipment. It is about the technician behind the bench. To excel in this craft—whether milling a complex zirconia bridge or casting a cobalt-chromium framework—a technician must possess a unique blend of technical and artistic skills.

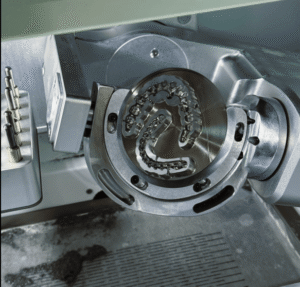

Before we examine the human element, however, we must acknowledge the mechanical foundation of the workshop. The heartbeat of the lab is often the steady hum of the air compressor. This unassuming machine powers the tools that bring our designs to life, acting as the silent partner in every fabrication step. From the precise air pressure needed for a dry milling spindle to the force required to blast investment material from a cast alloy, this utility is central to the workflow. But a machine is only as good as the operator. Here are the four pillars of a qualified dental technician.

1. Technical Instincts and Material Wisdom

A qualified technician possesses sharp “gut instincts” developed over years of practice. This is the intuitive ability to troubleshoot before a problem becomes a disaster. When dealing with diverse materials—be it the translucency of lithium disilicate, the brittleness of zirconia, or the toughness of cobalt-chromium—the technician must anticipate how the material will behave. They must understand, for instance, that the air compressor delivering clean, dry air is critical when milling zirconia to prevent micro-fractures, yet it is equally vital for the pressure-assisted casting of metal frameworks. The ability to foresee how a material will shrink during sintering or expand during casting is what separates a novice from an expert.

Large airflow volumes air compressor for dental laboratory casting, and dry milling workflow, source: https://www.dentallabshop.com/product/air-compressor/

2. Surgical Dexterity

While CAD/CAM has automated the heavy lifting, the human hand remains irreplaceable. Dexterity is the ability to manipulate tools with micro-millimeter precision. Whether using a pneumatic handpiece to grind a metal clasp or a brush to layer ceramic, the technician’s touch must be steady and controlled. The tactile feedback from an air-driven tool, powered reliably by that ubiquitous air compressor, allows the technician to feel the subtle changes in density as they finish a restoration. Without this fine motor control, even the most digitally perfect design can fail in the patient’s mouth.

3. Shading and Aesthetic Perception

The eye of the technician is the final judge of quality. This is where artistry meets science. Shading perception goes beyond just matching a color tab; it involves understanding how light interacts with different thicknesses of ceramic and the underlying core material. A technician must visualize the final result while the prosthesis is still a monochromatic block or a grey metal framework. They must know how to apply stains and glazes to mimic the natural fluorescence and opalescence of a tooth. If this perception is lacking, the restoration may technically fit, but it will never look “alive.”

4. Effective Communication with Dentists

Finally, a great technician is a great communicator. The lab is not an island; it is the backend of the clinical practice. A qualified technician must be able to interpret a dentist’s prescription—sometimes written in shorthand—and translate it into a physical reality. They must also know when to push back. If a dentist requests a long-span bridge in a material that isn’t strong enough, or if the margins on an impression are compromised, the technician must communicate this clearly and constructively. This dialogue ensures that the patient receives the best possible functional and aesthetic outcome.

Conclusion

In the end, the creation of dental prostheses is a symphony of elements. It requires the precision of a machine, the strength of the alloy, and the sensitivity of the artist. From the roar of the casting machine to the consistent hum of the air compressor, every tool relies on the technician’s guidance. By combining sharp instincts, steady hands, a keen eye, and open communication, the dental technician ensures that every restoration leaving the lab is nothing short of a masterpiece.